Final Report: Using a Human Security Lens to Examine the Mental Health Experiences of Somali Women Living in a Long-Term Displacement Camp, Kenya

Project Report

November 2024

Using a Human Security Lens to Examine the Mental Health Experience of Somali Women Living in a Long-Term Displacement Camp, Kenya

Grant

Using a Human Security Lens to Examine the Mental Health Experiences of Somali Women Living in a Long-Term Displacement Camp, Kenya. Funder: Mershon Center for International Security Studies. May 2022–April 2023 (extended April 2024). $17,000.

Research Team

Dr. Njeri Kagotho (MPI) Associate Professor

Ohio State University, College of Social Work

Dr. Gabriel Lubale (MPI) Coordinator

Kenya Institute of Migration Studies

Njoki Maina Gitau (Co-I and project administrator)

Researcher & Immigration Officer, Kenya Institute of Migration Studies Scholar, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Michael Ndurumo (Co-I) Professor

University of Nairobi, Department of Psychology

Executive Summary

This report provides a comprehensive overview of the outcomes and impact of this grant- funded project aimed at examining the lived experiences of Somali women living in Kakuma Refugee Camp.

Background

Humanitarian migration and mental health are intricately connected, making the lack of attention to mental health in global security discussions particularly concerning. Migrant women are considered especially vulnerable due to the distinct ways in which they experience the process of migration. Their intersectional identities, combined with societal expectations and gender roles, influence their mental health outcomes in unique ways. Studying the mental health experiences of female humanitarian migrants therefore demands a holistic approach, and this interdisciplinary team of researchers was well equipped to bring together diverse perspectives and expertise to address these complexities.

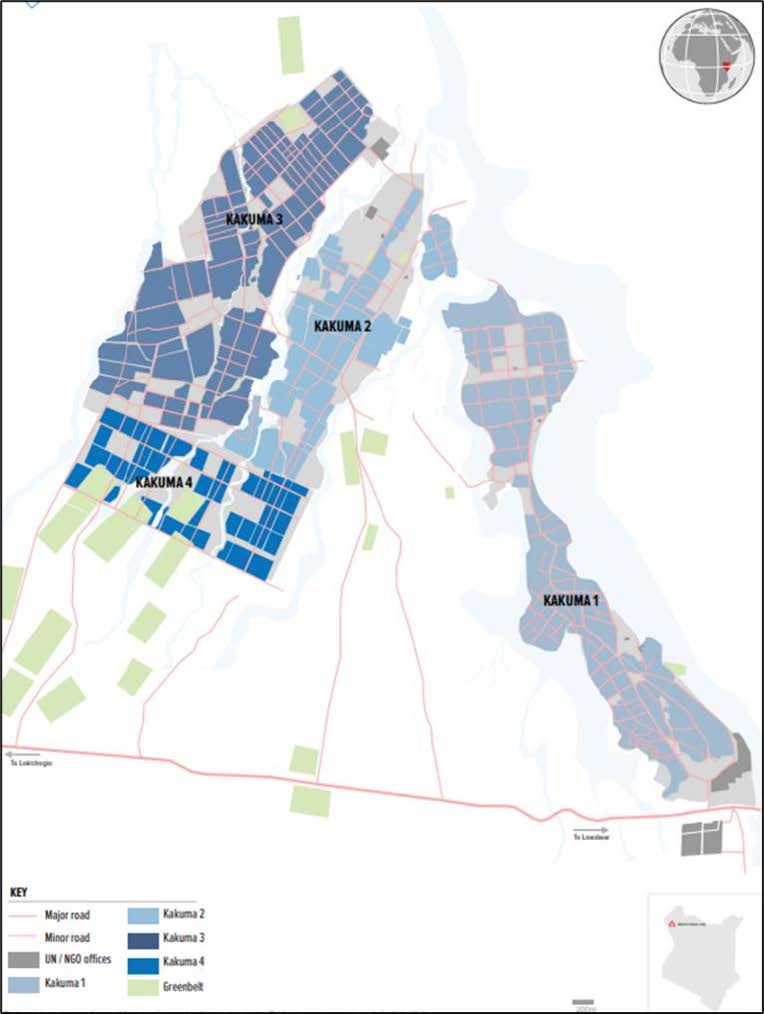

The site. Kakuma Refugee Camp, located in northwestern Kenya, covers an estimated 15 square kilometers. The camp hosts migrants from more than 20 countries, approximately 40,000 of whom are of Somali descent. Columbus, Ohio, is home to the second largest Somali community in the United States, and this connection to Ohio means the population has particular local interest.

Methods

Using a convergent mixed methods approach, this study examined mental health experiences of women residing in Kakuma Refugee Camp, with a particular focus on experiences of motherhood. Convenience sampling was used to enroll women of Somali origin (N = 260) to participate in the study in January and February 2024. A structured questionnaire of culturally and linguistically validated measures was administered by trained community health workers. In addition, a subsample of 15 new mothers was invited to participate in photovoice activities, which included short individual interviews and focus group discussions. Data transcription, translation, and cleaning was completed in April 2024.

Results

Preliminary data analysis reveals notable trends in how individuals engage in key services, highlighting both the strengths and areas for improvement within the existing support systems. We anticipate that the findings from this study will inform Kenya’s migration policy framework, including but not limited to addressing issues of service provision, encampment conditions, and resettlement procedures. The research team is currently working on analysis and dissemination, with one manuscript under review and one in preparation.

Challenges and lessons learned. Although the grant funding was awarded in April 2022, logistical, security, and climate-related concerns delayed fieldwork until January 2024. We appreciate the grant extension from the Mershon Center for International Security Studies, which enabled us to complete fieldwork despite these challenges.

Project Description

Humanitarian migration is a complex process involving legal, economic, and social challenges, as it seeks to balance the urgent needs of displaced individuals with the policies and capacity of the host country. Humanitarian migrants face cumulative migration stressors, which are further compounded by long-term stays in displacement camps. There are an estimated 122.6 million forcibly displaced persons worldwide (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], 2024b), making the mental health needs of humanitarian migrants of particular concern (Maleku et al., 2020). And because mental health concerns also present real global security threats, akin to communicable health crises, their absence in the global health security discourse is problematic (Beyer, 2017).

Using a mixed methods research approach, the study had three primary aims:

Aim 1 (QUANT): Examine the mental health functioning of Somali women

Aim 2 (QUAL): Use photovoice research methods to explore the everyday lives of Somali women residing in a long-term displacement camp

Aim 3: (QUAL): Describe the lived experiences of Somali mothers at risk of postpartum depression, through their positionalities as mothers, caregivers, and community members

We anticipate that that findings from this study will inform Kenya’s migration policy framework, including but not limited to issues related to service provision, encampment conditions, and resettlement procedures.

Background

Migrant women are considered a vulnerable population due to exposure to stressful premigration experiences, minority status, lack of social support, and challenges in accessing services in host communities (Bah & Kagotho, 2024). Pre-migration factors such as persecution, separation from family, violent conflict, and other traumatic events predispose humanitarian migrant women to significant mental health challenges. These factors are often heightened by post migratory experiences that may precipitate mental ill health, including economic, health, and political marginalization, which has further led to increased prevalence of psychological disorders (Mollica, 2001; O’Mahony & Donnelly, 2013).

The present study was informed by the human security paradigm (King & Murray, 2001), which defines human security as “freedom from fear and freedom from want.” Here, freedom from want includes liberation from chronic threats like environmental disasters, diseases, hunger, and famine, while freedom from fear focuses on individual safety and protection from personal or state-sponsored violence. Thus, human security is ultimately achieved by strengthening the resilience of communities (United Nations, 2016).

The literature is relatively silent on the relationship between mental health and global security, which is particularly concerning given that extensive mental health crises are often precipitated by global events such as acts of terror, pandemics, war, political upheaval, socioeconomic disruptions, and demographic changes. This notable gap in the literature,

especially in sub-Saharan Africa, underscores the need to further investigate the relationship between forced migration and mental health through a human security lens.

Kenya hosts more than 770,000 displaced persons of more than 23 nationalities. Many of these communities are in three key UNHCR camps: Dadaab refugee complex, one of the largest of its kind in the world, located in northeastern Kenya, and Kakuma Refugee Camp and the adjacent Kalobeyei Settlement, both located in northwestern Kenya. Kakuma Refugee Camp (Figure 1) includes four sectors and hosts approximately 88,206 humanitarian migrants from Somalia, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Republic of Kenya, 2024). This remote camp is home to approximately 40,000 individuals of Somali descent and has hosted them for 30 years.

While the UNHCR plays a critical role in the management and administration of the camp, Kenya’s national security organs are charged with guaranteeing security (Republic of Kenya, 2024; UNHCR, n.d.). The region's main police station is located within Kakuma town, serving Kakuma Refugee Camp and the Kalobeyei Settlement, and is supported by police posts situated within the camps. These security facilities, comprising both police station and police posts and patrol bases, form the backbone of the law enforcement infrastructure in the area.

Methods

Data collection took place in January and February 2024. We used convenience sampling methods to enroll women of Somali origin (N = 260) in the study’s closed-ended survey. In addition, a subset of 15 new mothers was provided with smartphones and invited to participate in photovoice and focus group research activities. Focusing on the Somali community aimed to provide a more nuanced understanding of the specific sociocultural dynamics that might be obscured in a broader study. Further, the community’s connection to Ohio made this population particularly interesting to the lead researcher. Columbus, Ohio, is home to the second-largest Somali community in the United States, making it a significant hub for Somali culture and identity.

Women were recruited from two villages (Kakuma 1 and Kakuma 3), which have a high number of Somali families. Data was collected by female community health workers who spoke two Somali dialects. Female interviewers were contracted, to enhance the comfort and openness of the participants, particularly when discussing sensitive topics such as interpersonal violence. In addition, because all the team members were community health workers with a basic understanding of trauma-informed care, they were well placed to foster an empathetic and supportive environment and to elicit more honest and detailed responses. All participants provided verbal consent prior to participation.

Research Ethics

The study was reviewed by the KNH-UoN Ethics and Research Committee and received research approval from the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation, and the Department of Refugee Services, Kenya.

Cultural Validation

To ensure culturally responsive procedures, the study team collaborated with cultural experts to inform the design, measures, data collection, and analysis plans. This included contracting a data management company that hires Somali researchers to provide transcription and translation services. In addition, several cultural experts were approached to review all research instruments, including Mr. Abdullahi Hillow Hassan, a social work lecturer and practitioner working for the Garissa County government.

Mitigating Risk

While this research did not present greater than minimal risk to participants, we acknowledged that there would be instances where mental health issues exceeding the expertise of the research team were identified. The need for referral mental health services is especially critical for individuals in long-term encampment who face rising levels of stress, trauma, and mental health challenges. The study partnered with International Rescue Committee (IRC) mental health clinicians in the camp to offer mental health services. Indeed, there were several instances when referral services were needed to enhance the continuum of care and ensure that women enrolled in the study received timely and comprehensive support.

Data Security

Thoughtful steps were taken to protect participant privacy interests: first, all data was collected on OSU Qualtrics, which prioritizes user privacy by implementing robust security measures; second, survey data was collected on study-provided, password-protected smartphone devices; third, survey and qualitative data was transferred and saved daily on secure OSU Microsoft 365 OneDrive servers; and fourth, women’s photography used as part of the data collection process was deidentified to ensure that no imagery contained identifiable information about individuals, protecting their privacy and confidentiality.

Preliminary Results

Two manuscripts currently in preparation focus on key findings from the study. The preliminary results provide valuable insight into women’s experiences in long-term encampment and their perspectives as mothers, caregivers, wives, and businesswomen. Initial analyses reveal notable trends in how individuals engage in key services, highlighting both strengths and areas for improvement within the existing support systems (Kagotho et al., in preparation; Kagotho et al., under review).

The average respondent was 35 years old (SD = 10.7, range = 18 to 67) and lived in households with an average of 7 individuals. Women have resided in the camp for between 1 and 28 years (M = 14.1, SD = 3.8). Slightly more than half the respondents did not report any formal education. More than half were married (n = 150, 57.7%), and of these, approximately 11.5% were in polygamous unions. The average household had a monthly income of 6,194 Kenyan shillings (approximately $50), with household incomes ranging from zero to 50,000 shillings (approximately $400).

Data indicates that economic precarity significantly impacts the well-being of participants, exacerbating vulnerabilities and hindering the ability of individuals and families to achieve stability and self-sufficiency. For instance, while food support through ration cards and food donations is provided within the camp, women reported that this food assistance lasted only halfway through the month, with 78% having to borrow money to meet household needs, thus highlighting the ongoing challenges they face in accessing adequate nutrition.

Approximately 31% of participants reported instances of violence and abuse. Analysis on interpersonal violence variables indicates that individual and household factors (marital status, age, and household food security) were associated with experiences of violence. Further, sociocultural and security factors (attitudes toward intimate partner violence, access to security services, and immigration services) also informed women’s experience of violence.

Photovoice Data

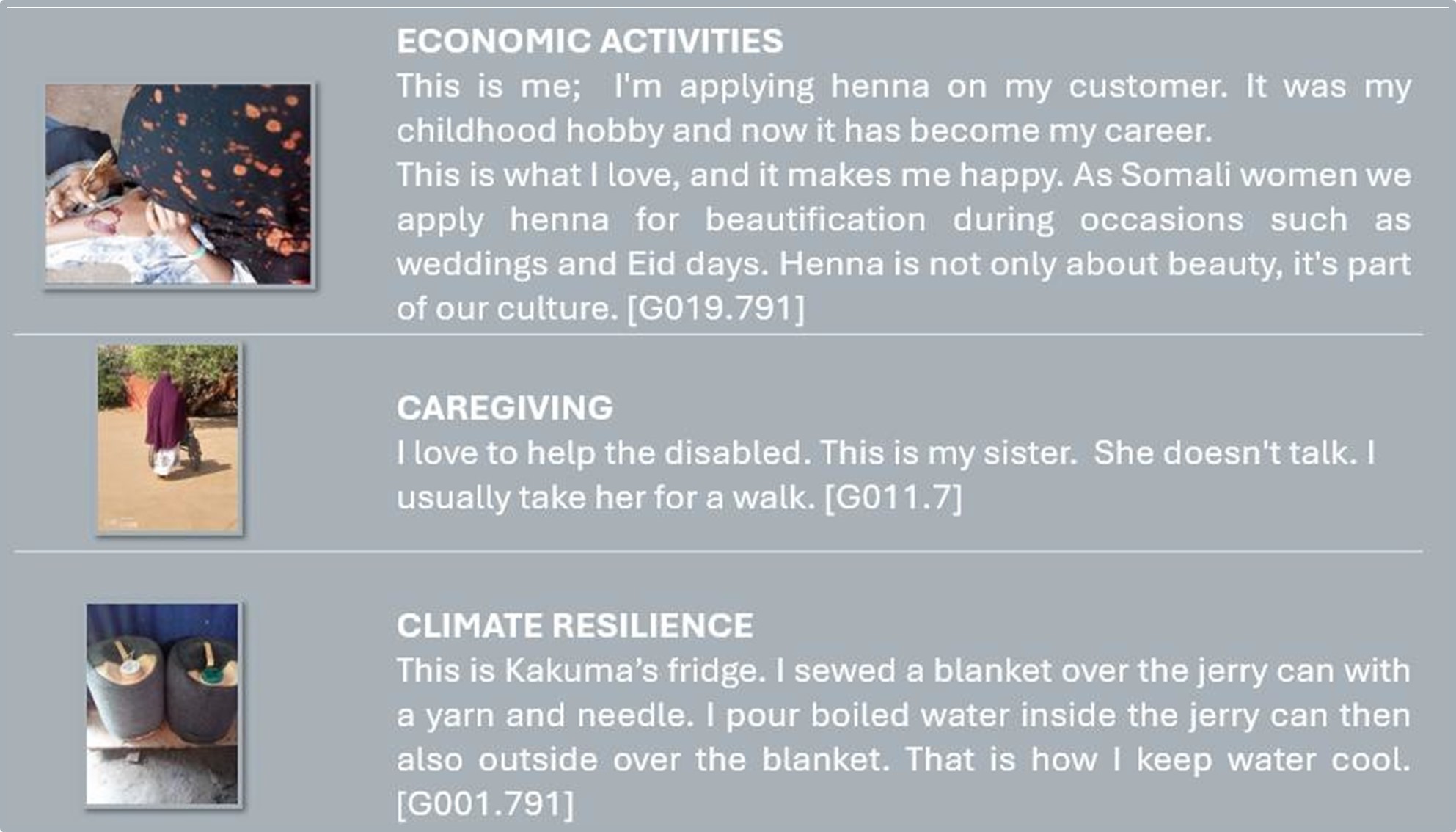

Photovoice data reveals hopeful narratives that highlight resilience, empowerment, and aspirations for a better future. Preliminary emergent themes revolve around economic self-sufficiency, caregiving, and climate resilience.

Through photography and accompanying focus group discussions, these new mothers showcased moments of joy, love, and beauty in their primary role as caregivers. Mothers demonstrate remarkable economic prowess and an entrepreneurial spirit to leverage sustainable livelihoods for themselves and their families. Kakuma Refugee Camp, like many other humanitarian camps, is located in an area prone to extreme weather conditions, such as floods, droughts, and heat waves. Women illustrated intergenerational and community strategies used to adapt to these conditions. Finally, though it is not captured in the data, anecdotal accounts from some of the women pointed to the transformative nature of the smartphones they received from the study.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

Interdisciplinary research projects such as this one provide powerful learning opportunities that are invaluable for future research pursuits. By reflecting on the lessons learned, we can contribute to better fieldwork preparedness and effective collaboration.

Future Studies

These findings, combined with discussions between Drs. Lubale and Kagotho and immigration officers, health care providers, and business leaders in Kakuma, revealed several key knowledge gaps that warrant further attention. Notably, the importance of trauma-informed training and practices for immigration and border officers emerged as a critical area for future focus. Immigration officers, who often are the first point of contact for humanitarian migrants, play a crucial role at the intersection of national geopolitical concerns, international policies, and individual well-being. As such, a trauma-informed approach is essential in their work and would help them to recognize and respond sensitively to signs of distress and fear that arise from migrants’ traumatic experiences. During a dinner hosted for 12 immigration officers stationed at Kakuma Refugee Camp, Lokichogio, and the Nadapal border crossing along the Kenya–South Sudan border, engaging discussions led to the formulation of a compelling research question: How can trauma-informed practices be integrated into immigration services to improve the support and outcomes for individuals experiencing trauma at border crossings? The research team is in the process of identifying potential funding sources to address this question.

Unintended Consequences of Smartphones

Smartphones offer several significant benefits to women in low-income communities, serving as powerful tools for networking, economic empowerment, and access. Anecdotal information from the women we interviewed and from the data collection team points to an unintended consequence of smartphones provided as part of the study. Women who previously lacked access to personal phones expressed that having the device would greatly enhance their ability to communicate with family and friends, both within the camp and around the world. Additionally, women noted that smartphones would support entrepreneurship by providing access to mobile money and other technology-based financial services widely used in Kenya.

Interagency Collaboration

Interagency collaborations in research foster partnerships that expand access to resources and address complex research challenges by employing diverse expertise and perspectives. Two key partnerships were established and nurtured in the course of this grant, with the Kenya Institute of Migration Studies (KIMS) and the International Rescue Committee (IRC)– Kenya.

Kenya Institute of Migration Studies

KIMS is a regional center for migration research and postgraduate studies. The institute is charged with training migration and security officers from Intergovernmental Authority on Development countries in East Africa. In partnering with KIMS, the study was able to obtain necessary government permissions to access Kakuma Refugee Camp and Kalobeyei Settlement. Dr. Lubale (MPI) facilitated open channels of communication, granting the study access to the resources required to address practical challenges in the field. Additionally, this partnership allowed the study to align its approaches to the country’s immigration agenda.

International Rescue Committee

By leveraging her networks, Ms. Njoki Maina-Gitau (Co- I) established a collaborative relationship with the IRC, an intergovernmental organization founded in 1933 that provides health care, education, and empowerment interventions with a focus on the unique needs of at-risk women and girls. Since it began operations in Kenya in 1992, it has served more than 500,000 refugees and asylum seekers. The IRC’s expertise in supporting at-risk and vulnerable humanitarian migrants, its strong presence in Kakuma Refugee Camp, and its focus on addressing the unique needs of women made it an ideal partner for collaboration. Women in need of mental health supports and those in immediate distress were referred to IRC mental health providers. In addition, the organization played a crucial role in addressing security concerns. The research team gained access to UNHCR flights to and from Kakuma through the IRC, which helped minimize the security risks associated with road travel. Additionally, the IRC facilitated connections to vetted car companies, ensuring the team had reliable 4×4 off-road vehicles, necessary to navigate the difficult terrain.

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic presented numerous challenges to our research project, significantly impacting both the methodology and the timeline. The Ohio State University’s travel restrictions and logistical complexities necessitated a delay in the start date, preventing us from conducting fieldwork as initially planned. The pandemic significantly impacted the cost of electronic devices, primarily due to disruptions in supply chains and increased demand for technology. The significant cost increase placed a constraint on the number of smartphones the study could purchase, necessitating a decrease in the photovoice sample size from 24 to 15 new mothers.

Safety Concerns

The study team encountered several safety and security challenges during both the planning and the execution phases of the research. In 2023, there was an increase in bandit attacks and warnings of potential terrorist threats in northern Kenya (Armed Conflict Location and Event Data, 2023), which affected travel plans. Additionally, Kakuma Refugee Camp experienced severe flooding, displacing a portion of its residents (UNHCR, 2024a). As a result, the camp was placed under lockdown, and humanitarian efforts were redirected to prioritize assistance for the displaced families in the camp.

Conclusion

This grant-funded project underscores the complex challenges and opportunities in refugee camps like Kakuma Refugee Camp, highlighting both the resilience of women and the critical supports available in the service systems. Moving forward, it is imperative that researchers, service providers, and governments work collaboratively to ensure that refugee camps foster healing, dignity, and long-term integration.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Kakuma research team’s unwavering dedication and resilience throughout the data collection process. Their professionalism and tireless efforts even under challenging work conditions made this study possible. We also acknowledge the concerted efforts of the entire KIMS team. Their work behind the scenes to ensure open communication channels between the study team and various collaborative partners, allowing the research team to leverage their extensive networks within government agencies, and their administrative supports contributed to the success and fruitful realization of this study.

We extend our heartfelt thanks to our in-country service providers, including Jesuit Refugee Service–Kakuma, for providing comfortable training and research facilities; Jostar Legacy Investments for providing transportation and security services for the duration of our field work; and Linda Munga Company for their excellent translation and transcription services, which were instrumental in ensuring the accuracy and clarity of our data. Finally, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to the College of Social Work’s business office, whose diligent work and expertise in managing the postaward grant funding have been invaluable to the success of this project. The team ensured that all financial processes were handled with the utmost expediency, navigating complex international funding requirements while ensuring compliance with grant regulations. Photo: Research team of (left to right) Farhiya, Fatuma, Sagal, Njeri, Fatuma, Aniso, Farhiyo, and Leila.