Five Ways the National Security Simulation Prepares Students for Careers in Government and Media

On November 5, 2021, there was a terrorist attack at a courthouse in Medina, Ohio, a ransomware cyber attack that shut down Google Voice services, and armed extremist militias battling in Columbus. The next day, there was a new strain of COVID detected, an international security crisis between NATO and Russia in the Arctic, and a nuclear plant in Ohio that was on the fritz.

Quite the weekend.

While this didn’t happen in the real world, of course –it did all occur during The Ohio State University’s National Security Simulation supported by the Mershon Center.

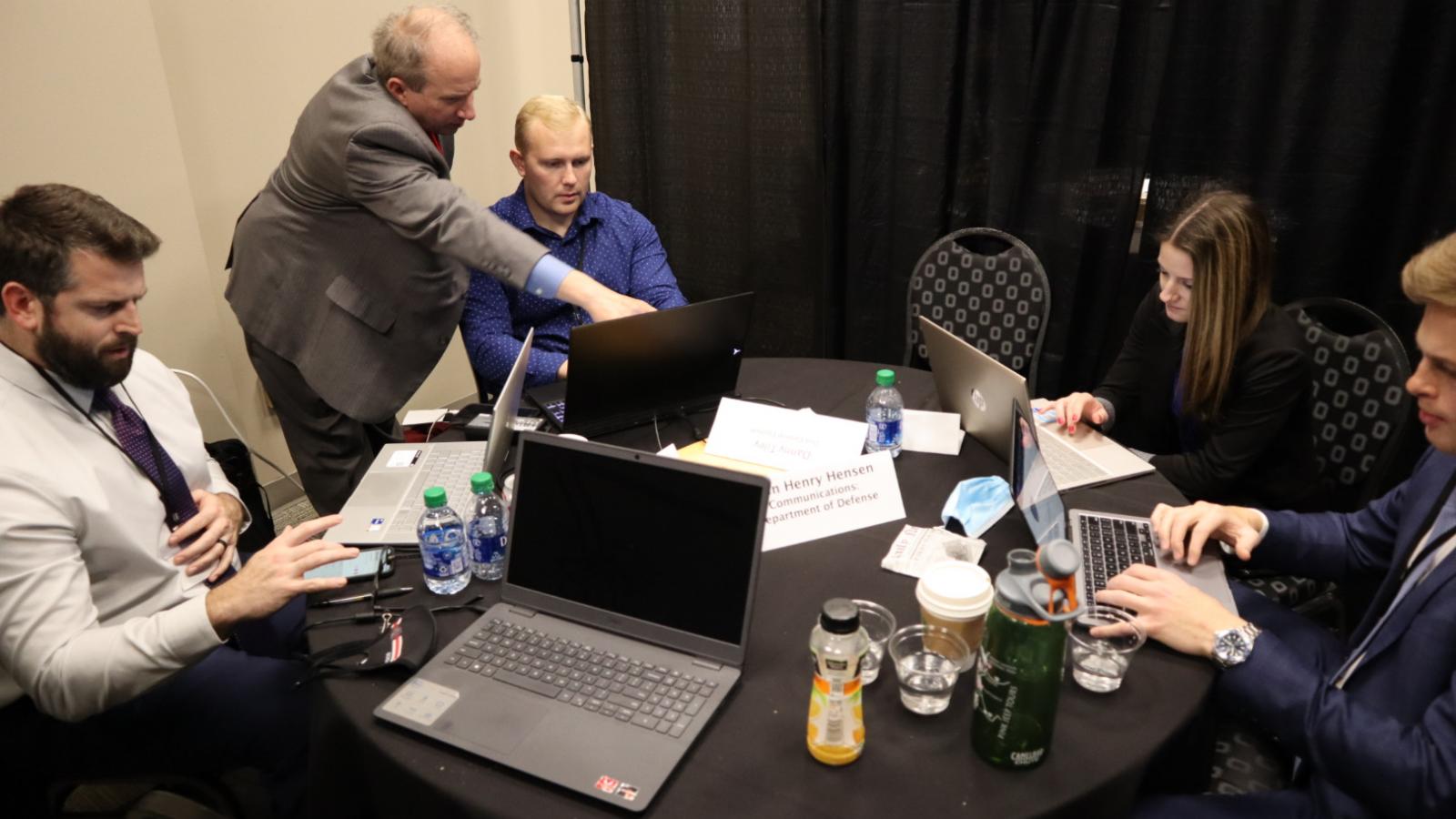

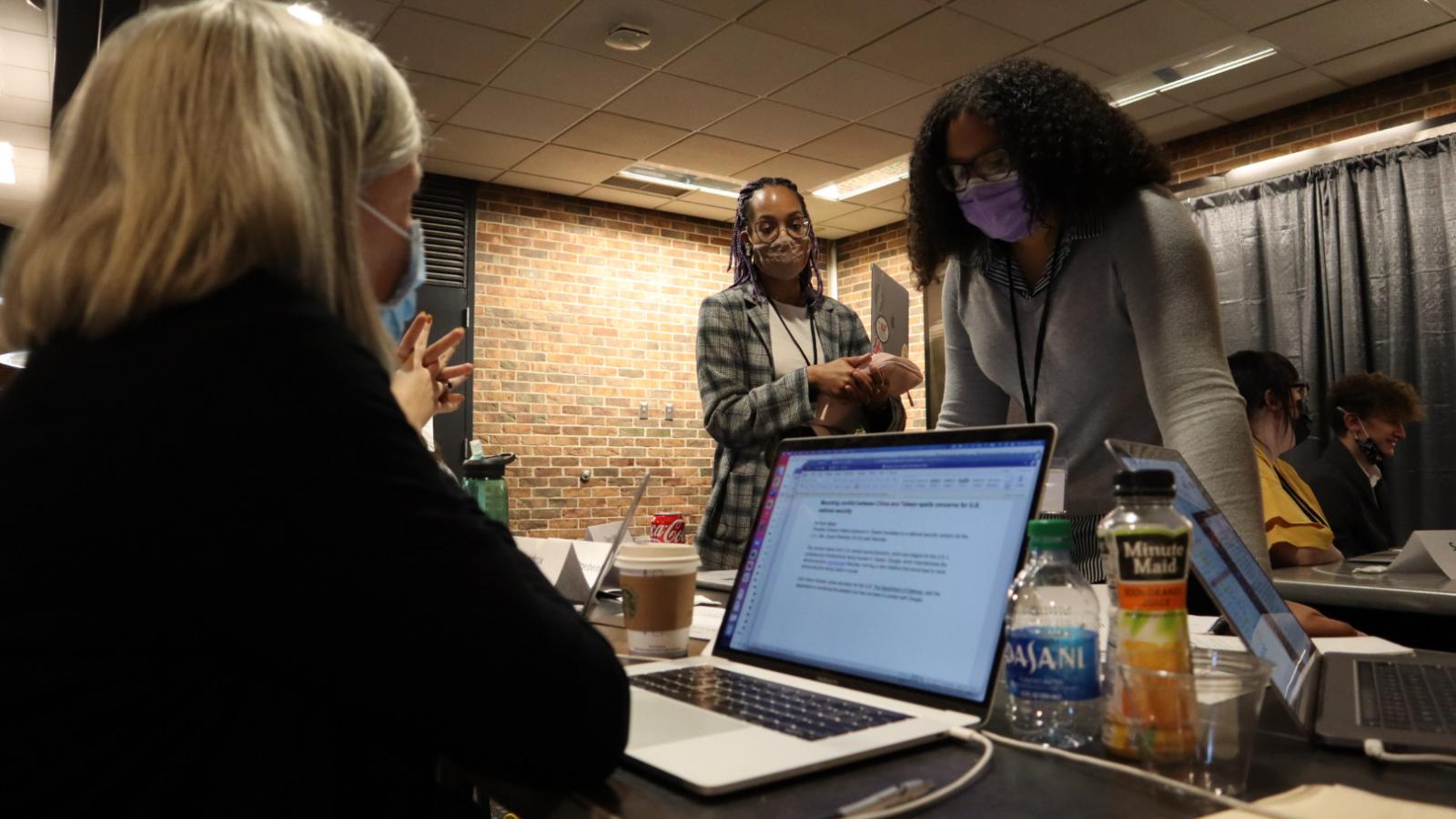

The National Security Simulation is a two-day exercise that puts students in real-world government, media, and private sector roles to train their professional skills as they manage a seemingly endless – but very real -- series of crises.

This year’s simulation was the fifth and largest in the innovative program’s history, with over 180 participants. A couple dozen were on the simulation’s “control team,” which used intelligence and media injects and in-person role-play to present players with intelligence puzzles and drive them toward consequential decisions. Most the Simulation’s participants were the players – both practitioners in the most senior roles and students in advisor roles – who role-played alongside each other in government and non-government positions. The practitioners modeled professional decision-making, while the students got to see them in action and hone their skills in advising busy senior leaders who can seem very intimidating to students and recent graduates just starting out.

Aside from being the largest and most complex simulation to date, this was the first year students from other universities were invited to participate. Other students came from Purdue, Otterbein, Dayton, Cincinnati, and Ohio Universities.

Dakota Rudesill, professor in the Moritz College of Law and senior faculty fellow with the Mershon Center, is the mastermind behind the simulation and all of its real-world scenarios thrown in to stir challenge the players.

“The simulation trains several communities of students in foundational and transferrable professional skills, starting with role assumption,” said Rudesill. “Additionally, this immersive simulation model teaches-by-doing other practice skills that are transferrable to any professional setting, including teamwork across institutional and professional lines, working with senior leaders, short-form written and oral briefing, use of process in decision-making, time management, dealing with rapid change, and acting with integrity despite pressures of time, uncertainty, and personality.”

Here are five of the top ways the simulation gives students an invaluable experience for careers in the real world.

1. Encouraging Students to Play Their Position and Find Their Voice

Assuming a role, with a practitioner as their boss and particular authorities to act, provides students a very real-feeling sense of responsibility as real-world crises unfold. In this simulation setting, the various scenarios gave nearly every player an opportunity to be a decision-maker or advisor and to take initiative.

“It was amazing to see these students really assuming their roles and pushing back on strategy decisions, even when they were working with some pretty experienced practitioners,” said Kelly Whitaker, communications specialist with the Mershon Center and one of the practitioners mentoring students during the simulation. “They weren’t intimidated by the crisis or people they were working with. It was really impressive.”

2. Working with Senior Leaders, and Networking

Speaking of working with experienced practitioners, this year’s simulation featured a list of dozens of impressive volunteers who assumed top leadership roles and worked directly with student players. Students learned-by-doing how to find their footing in dealing with practitioners who are decades more experienced, move quickly, and often either have a very different professional background. Just a few of these practitioner volunteers participating this year included:

- Corin Stone: Former NSA Executive Director & Deputy Director of National Intelligence (DNI), and currently Senior Fellow at American University’s Washington College of Law. Role-played as DNI.

- Colleen McMahon: Senior Judge, U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York (S.D.N.Y.). Role-played the federal district & FISA court judge.

- Larry Obhof: Former President of the Ohio Senate, and currently Partner at Shumaker, Loop & Kendrick LLP – Role-played the U.S. Senate Majority Leader.

- Heidi Heitkamp: Former U.S. Senator -- Role-played the U.S. Senate Minority Leader.

- Philip Bump: Washington Post reporter – Role played himself.

- Maj. Gen. Mark Bartman (USAF, Ret.): Former Adjutant General of Ohio -- Role-played the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Additionally, former Acting and Deputy CIA Director Michael Morell keynoted the first day, addressing some of the most difficult decisions he faced during his career and the challenges national security professionals will face in the years to come.

3. Grappling with Real Issues and Decision Processes

“The Simulation picks up with the real world as-is, so that the players can bring to bear all that they know about real world fact, policy, and law,” said Rudesill. “And with these realistic scenarios, students experience firsthand the complexity and volatility of the international and domestic security environments, public policy processes, and public-private sector relationships. They see firsthand how actors in national security operate in the context of the daily press and intelligence cycles, and in the context of a half dozen or so intersecting decision processes, at the agency, inter-agency, inter-branch, federal/state/local, and international levels.”

This year’s key scenarios included:

-

Congress debating and repealing the now 20-year-old post-9/11 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), plus two other AUMFs concerning Iraq, from 1991 and 2002

-

Federal and state government working with the private sector to deal with a ransomware cyberattack

-

Government applications for surveillance of suspected foreign agents

-

Court review of government decisions about detaining a self-radicalized terrorism suspect

-

Government decisions about what to do about a foreign terrorist leader, where intelligence is sketchy and the risk to civilians could be very real

-

An international security crisis between NATO and Russia in the Arctic

In addition to these examples, there were a number of intelligence puzzles for the players at intelligence agencies to untangle while there was still time to act.

4. Practical Application of Skills

The Simulation bridges the classroom and the real world. Students are able to use skills they have learned in class – such as intelligence analysis, legal analysis, and military strategy -- and apply them in real time to real-world scenarios. Even in internships, students may never be able to meaningfully utilize some of the skills they learn about because interns are often not allowed to participate in high-level meetings or handle the kind of crises senior decision-makers grapple with every day.

“These two days spent in the 'sim' taught me skills applicable to jobs I may have in the future, like communicating with journalists, problem solving under strenuous situations, and maintaining transparency with the public,” said Tristan Monteith, a third-year OSU undergrad. “As I want to attend law school and obtain my master’s degree in public policy, I may eventually work in the public sector as a policy assistant to an elected official and this simulation gave me valuable, individualized experienced I can take with me.”

5. Risk-Free Learning

At the core of the simulation is a learning experience. And the students who participated were able to practice professional skills, make mistakes and ultimately learn from everything they did during the simulation with no consequences. While some of the decisions if made in real life could have had undesirable outcomes, here errors – such as an accidentally leaked classified document – are embraced as learning opportunities. As Professor Rudesill noted, “the Simulation allows students to have those stressful, unforgettable, and valuable experiences in the safety of an off-the-record academic environment.”

The next simulation will likely be planned for 2023 and we can expect that to be an even larger and complex production. For more information on the simulation, you can visit the program's webpage here.