Mershon and College of Public Health hosts Virtual Symposium, The Far-Right: Examining its Roots and Challenging its Reach, with Plans to Build a Community Consortium to Address Concern

On October 12 and 13, the Mershon Center and the College of Public Health are hosting the virtual symposium, The Far-Right: Examining its Roots and Challenging its Reach. This symposium is organized by Laura Dugan, Ralph D. Mershon Professor of Human Security and Professor of Sociology and Victoria Gurevich, PhD Candidate from OSU’s Department of Political Science.

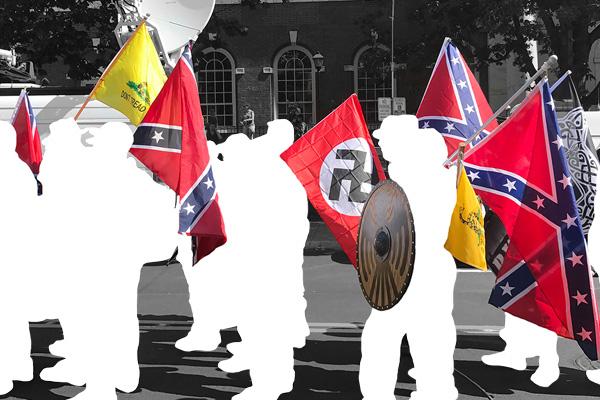

The idea for this symposium formed after we recognized the disconnect between American’s surprise by the January 6th attack on the U.S. Capitol and its conspicuous inevitability due to mounting tension by disparate elements of the far-right through increasingly violent Stop the Steal rallies and online forums. Even if we ignore post-election grievances, the rising threat of far-right violence in the U.S. combined with rally cries from the sitting U.S. president made something like what we saw that day inevitable. Far-right attacks, murders, and other hate crimes have gained momentum since the election of Barack Obama, surpassing any other ideological threat to Americans. White supremacist organizations and other far-right groups have long called for a race war and a chance to overthrow the government. The growing political legitimization of fringe ideals and calls to stop the certification of Joe Biden as president is the nearest the far-right would be to achieving its military ambitions. They were ready.

Despite all of this, people were still shocked to see the violent mob of mostly White Americans try to overthrow the government that day. We expect that this shortsightedness is likely due to the little attention given to the far-right threat in the U.S. by our leaders, the media, and our schools. Historic evidence undeniably shows that key elements of extremist ideas today were routinely expressed in ordinary conversations between White Americans in earlier decades and centuries. When such ideas have been a part of our shared history since colonial times, it is difficult to recognize its ubiquitous danger today. Historic tolerance for white supremacist ideals paired with emerging technologies, globalization, and novel crises encourage the spread of far-right ideologies.

To be clear, the far-right problem in the U.S. is not due to Donald Trump and his most vehement supporters. Donald Trump and his supporters are a symptom of a growing momentum of far-right ideals in the U.S. and elsewhere. While he has had a mobilizing effect on the movement, far-right extremism was a problem long before Trump and it will continue to be a problem after he is gone. The next generation of far-right politicians are winning consequential offices, hundreds of law enforcement and military personnel have been found on the membership rolls of groups such as the Oath Keepers, and the recent public health crisis has entrenched among people a conspiratorial mindset that serves to undermine democratic institutions.

Furthermore, this problem extends well beyond the U.S., as far-right parties have achieved substantial power in European parliaments. Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, and his Fidesz party are seen as models to other far-right movements in Europe as they passed laws that undermine democratic ideals, effectively detaining all migrants and threatening the well-being of Muslims, Roma, and other minorities currently living in Hungary. In South America, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has become the model for other rising far-right politicians, gaining momentum among voters in Argentina and Chile. Even countries that have overcome white supremacist governments, like South Africa, struggle with removing its racist legacy from its institutions. In order to challenge this growing threat, we must understand where it comes from, how it works, where it has gone, and where it might be heading.

As such, we organized this symposium with three goals in mind. First, we want to hear from scholars and other experts who study early components of what has evolved into the far-right in the U.S. and across the globe, how these ideas are spread, and to where the far-right is infiltrating. To that end, the symposium features presentations from twelve researchers who will speak about different elements of far-right movements in the U.S. and elsewhere. Second, we want to involve people with first-hand and professional experiences with extremism to respond to the presentations. Four responders, with perspectives from the vantage point of federal government, local politics, public health, and personal experience, will bridge the gap between research and practice. Third, after hearing from everyone, we want to brainstorm on actions steps in order to curb the far-right momentum. Guided by questions from the audience and from the facilitators, the final panel will bring presenters and respondents together into an open conversation about what can be done. Finally, the task of challenging extremism is not over when the symposium ends. We aim to form a coalition of concerned folks to keep this effort going by informing the broader community, connecting persons with similar concerns, and to empowering members to preserve democratic ideals.