Postdoc Blog: Emily Hardick on “Experimental Theater, International Collaboration, and the Spatial Imaginary of Mobutu's Zairian Authenticité Campaign.”

At our Mershon Monday event on March 17, Emily Hardick presented her Mershon-funded research on the relationship between the international mobility of performers and cultural diplomacy in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Her talk, which focused on Experimental Theater, International Collaboration, and the Spatial Imaginary of Mobutu’s Zairian Authenticité Campaign, is part of her doctoral dissertation based on the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The dissertation examines the international tours of Congolese performance troupes, their relationships with Belgian arts organizations, and their role in the performance of colonial subjecthood and postcolonial national identity from the 1930s to the early 1990s.

Using the concepts of mobility and authenticité, her work highlights how performers translate onstage movement to offstage mobility across local and international borders, and how authoritarian governments use dance and performance in the control of citizens. According to Hardick, the concept of authenticité constitutes a layered ideology formulated by intellectuals and propagated by the DRC’s Movement Populaire de la Révolution (The Popular Movement of the Revolution, or MPR). In the DRC, authenticité served as a colonial construction, a postcolonial tool of legitimation, and an avenue of professional and artistic mobility. Another often overlooked perspective of authenticité “from below” is that it was met with responses ranging from modest enthusiasm to skepticism and even outright irony.

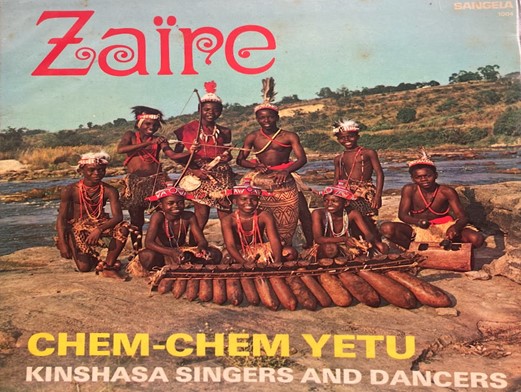

In both colonial and postcolonial contexts, Congolese performers interacted with broader ideas of African “authenticity” and relationship to place in diverse ways, pursuing bodily autonomy and free movement. Although governmental controls constrained performers such as Chem Chem Yetu, they continued to exercise “unique mobilities,” including participating in imperial and international tours to European countries. As Hardick argued, Congolese performance and theatre arts in these contexts often transformed into networks of professional activities, rather than solely representing instruments of state control.

During the colonial period, Catholic missionaries such as Father Bernard Van Den Boom organized troubadour troupes and international collaborations with various groups in setting up Congolese performers’ international tours beyond Kinshasa. While a group of young male Congolese performers known as The Troubadours of King Baudouin had traveled to Belgium for the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, Van Den Boom worked hard to create new international collaborations beyond colonial networks for Congolese performers. For example, through his efforts, another Congolese troupe, the Petits Chanteurs et danseurs de Kenge (the Little Singers and Dancers of Congo), toured Belgium, Italy, Switzerland, and Canada in 1967. Upon returning from these tours, Ben Van den Boom founded a Kinshasa-based Chem Chem Yetu (see a picture below).

Chem Chem Yetu was caught up in Mobutu’s “Recourse to Authenticity” campaign through which the Mobutu government used music and dance as tools for political organizing and regime legitimation. Mobutu’s regime became hugely invested in cultural institutions and cultural production as part of the Zairian Authenticité Campaign project. This approach led to the incorporation of young performers into the junior wing of the Mobutu-led MPR. Chem Chem Yetu performed at the MPR’s headquarters in the mid-1970s and the Inga Dam Project Celebrations, earlier in 1972. While they were used to support Mobutu’s postcolonial socio-political project, performer groups like Chem Chem Yetu also continued their international mobility and developed their professional aspirations, touring Germany, Milan, and Rome, all in 1973. What is interesting about the international tours and performances of Congolese troupes is that while they did troubadour performances, they also had an interest in traditional dance.

Hardick uses innovative methodologies, arguing that “mobility” must be more clearly theorized in the absence of well-documented tour itineraries for Congolese troupes. In the absence of “mappable” archives such as tour itineraries in the DRC and Belgium, Hardick conducted Mershon-funded fieldwork in the DRC, where she used a range of ethnographic methods, including interviews with performers such as François Debs. She also examined the visas, family photographs, and travel clippings shared by Debs. These methods revealed an interesting temporal dimension to understanding performers’ mobility, as aspirations of travel increased further in the 1990s when new state agencies in France, Belgium, and other EU countries began to support African dance.

Mershon Monday Story by Postdoctoral Fellow Nicholas Nyachega, in collaboration with colleagues Julia Marino and Helen Murphey.