Postdoc Blog: Jacien Carr on Poro Power Association and the First Liberian Civil War (1989–1997)

At our Mershon Monday event on March 3, Dr. Jacien Carr presented his research on the Poro (men’s power associations) history, folklore, and warfare during the First Liberian Civil War (FLCW) from 1989 to 1997. The parallel women’s power associations are called Sande in Liberia or Bundu in Sierra Leone. While his talk focused largely on Liberia, his broad research explores the central role of Poro beyond the borders of Liberia, including Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Côte d’Ivoire. In these countries, Poro plays an important role in guarding, mobilizing, and transmitting esoteric knowledge. They are the institutions through which societies are organized and governed. In Liberia, Poro is practiced by ten of Liberia’s fourteen major ethnic groups.

Based on examining Poro’s history, folklore, material culture, archives, and oral histories, Dr. Carr argues that a credible case can be made that the FLCW began as a National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) insurgency facilitated by a Nimba Poro insurrection. The current consensus is that Poro involvement in the conflict was incidental and not a coordinated effort between the organization and the NPFL. Carr’s contention is that in the initial stage of the war, Poro ethnic Gio members of Nimba partnered with the NPFL using Poro’s capacity to mobilize its members for social causes. In so doing, Nimba Poro associates sought to avenge the 1986 attack on their homeland by President Samuel Doe and his ethnic Krahn-dominated Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL). In the process, they also hoped to protect their community by initiating NPFL fighters into Poro to control the violence.

Before the FLCW, President William V. S. Tubman (1944–1971) recognized the necessity of forging an alliance with Poro to govern effectively in Liberia. Upon deciding that he could not construct a unified nation without the support of Poro, Tubman journeyed into the interior, underwent initiation, and formally joined. Since Tubman’s tenure, every Liberian president (except possibly George Weah) has been initiated into Poro. This would also include Africa’s first democratically elected female head of state, Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, who is reported to have been initiated into Sande.

The FLCW gradually consumed much of Liberia, with various warring factions and combatants pursuing their own interests. While the latter stage of the fighting has characterized our understanding of the conflict, Carr’s position is that the FLCW owes its inception to an NPFL/Poro alliance in 1989. By the time Doe’s grip on power faltered and Charles Taylor emerged as the central rebel leader, Poro networks had already shaped the war’s early alliances. The war’s earliest phase stands as a testament to how deeply Poro influenced the conflict, whether in clandestine gatherings or in the ranks of the child soldiers it quickly initiated. Although at the end of the war and during his tenure, Taylor himself focused on power rather than preserving indigenous institutions—and may not have cared about the society’s deeper traditions—the presence of Poro members within NPFL ranks blended spiritual authority with military might.

From the immediate aftermath of the FLCW to the present, Poro remains one of the most powerful institutions in Liberia and Sierra Leone. As Dr. Carr argued, Poro has a longstanding tradition of social engineering, and it has not only influenced politics through sacred rituals and initiations but also mobilized communities toward shared objectives. Whether in times of peace or conflict, Poro’s ability to unite disparate groups under its umbrella makes it a formidable force in political and social life in Liberia and its neighboring countries.

Dr. Carr’s research methods raise questions about innovative research approaches and ethics, revealing the challenges and opportunities that scholars may encounter in carrying out research on closely guarded traditions. In Liberia, because Poro preserves secret knowledge and ensures continuity across generations, it is risky for “outsiders” to access Poro practitioners and their knowledge. Because Dr. Carr is from Liberia, he used his cultural and political knowledge, as well as family networks, including his late cousin, to gain access to Poro insiders’ “secret knowledge” during his fieldwork. He also protected Poro’s “secret knowledge” by not naming the practitioners and not providing the full details of their activities.

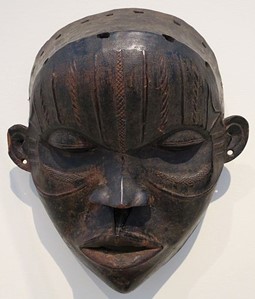

In addition to underscoring the nexus between Poro, history, and warfare, Dr. Carr highlighted the misconceptions regarding Poro and the changes that Poro regalia has undergone across space and time. Although some scholars and observers have misconstrued Poro as demonic, Dr. Carr argued that Poro is a secret power institution through which societies are organized and governed, not a demonic organization. The misunderstanding about Poro arises from the fact that outsiders, especially European missionaries, anthropologists, and sociologists, viewed Poro through a religious and cultural lens. Yet Poro is not a religious organization, though it derives power from cosmological beliefs shared by various ethnic groups. In addition, the Poro mask has been misunderstood by outsiders, who tried to connect these masks to other traditions and material cultures across and beyond the continent. Yet, within Poro, the mask serves as a conduit of spiritual or cosmic force. To outsiders, these masks may seem like artifacts, but for Poro experts, they embody spirits, each requiring specialized knowledge to interpret. The masks were modified over time based on the circumstances and the message Poro practitioners were communicating.

Mershon Monday Story by Postdoctoral Fellow Nicholas Nyachega, in collaboration with colleagues Julia Marino and Helen Murphey.

Image credit: Palm Nut Harvesting on 50 Dollars 2009 Banknote from Liberia (courtesy of iStock).