Postdoc Blog: Laurie Georges on the Feedback Loop of Erasure

At our Mershon Monday event on March 31, Laurie Georges, a PhD candidate in Political Science, presented her research on the mechanisms of erasure: the intentional removal of peoples and their traces from their territories. Rather than constituting a single moment of violence or rupture, Georges’ findings conceptualize this as a process with numerous reverberations.

Georges argues that the feedback loop of erasure begins with an initial act wherein a host state erases a linguistic, religious or ethnic minority group. This erasure may include material violence and displacement, but also includes more symbolic dimensions aimed to create a structured ignorance among the population of the host state, such as cartographic changes, historical revisionism and heritage destruction. Georges’ findings distinguish the mechanisms of erasure from standard nation-building, as erasure involves the deliberate attempt to materially or symbolically remove internal minority groups.

In her theoretical framework, erasure heightens threat perceptions and produces irreconcilable identity narratives for both majority and minority groups, entrenching nationalisms. This initial erasure triggers a series of indirect effects, which are international as well as local: Georges suggests that it may trigger other countries to begin processes of erasure towards their own minority groups. Yet this fear of erasure may also cause other minority groups to feel threats more acutely, encouraging them to mobilize, which highlights them as existential threats. Lastly, Georges identifies a series of interaction effects, another type of reverberation. These may occur when displaced groups move or are moved into different states, where this experience of trauma and erasure structures their interactions with other actors, including the international community.

The primary case study that Georges explores is the Armenian genocide of the early twentieth century and its reverberations in subsequent Armenian-Azerbaijani conflicts. For example, when the Soviet Union gave Nagorno-Karabakh, a region with a large Armenian majority, to Azerbaijan in 1923, it intensified Armenians’ existential threat perception due to the violence experienced during the genocide. At the same time, another reverberation manifested in how early Azerbaijani nation-building became interrelated with Turkish nation-building in response to this history and how it was later shaped by Armenian demands.

In another example of a reverberation, Georges’ research also explores how this erasure has affected Turkish-Kurdish relations. She argues that one of its indirect effects was prompting the Kurds to anticipate their own erasure, therefore causing them to advocate for greater autonomy. This intensified conflicts with the Turkish state, which were exacerbated by the homogenizing conceptualization of identity and assertive nationalism adopted and promoted by the Turkish government. In exploring the linkages between the national and transnational, Georges identifies and examines another indirect effect: how this impacted how Iran, Iraq and Syria treated Kurdish minorities within their own territories.

Through identifying and tracing these indirect effects and reverberations, Georges’ research illustrates how the impacts of erasure spread across borders and throughout history. This deepens our understanding of the frequently contested intersections of identity and nationalism, and highlights how international, state and non-state actors contribute to narrating and contesting historical memory.

Mershon Monday story by Postdoctoral Fellow Helen Murphey, in collaboration with colleagues Julia Marino and Nicholas Nyachega.

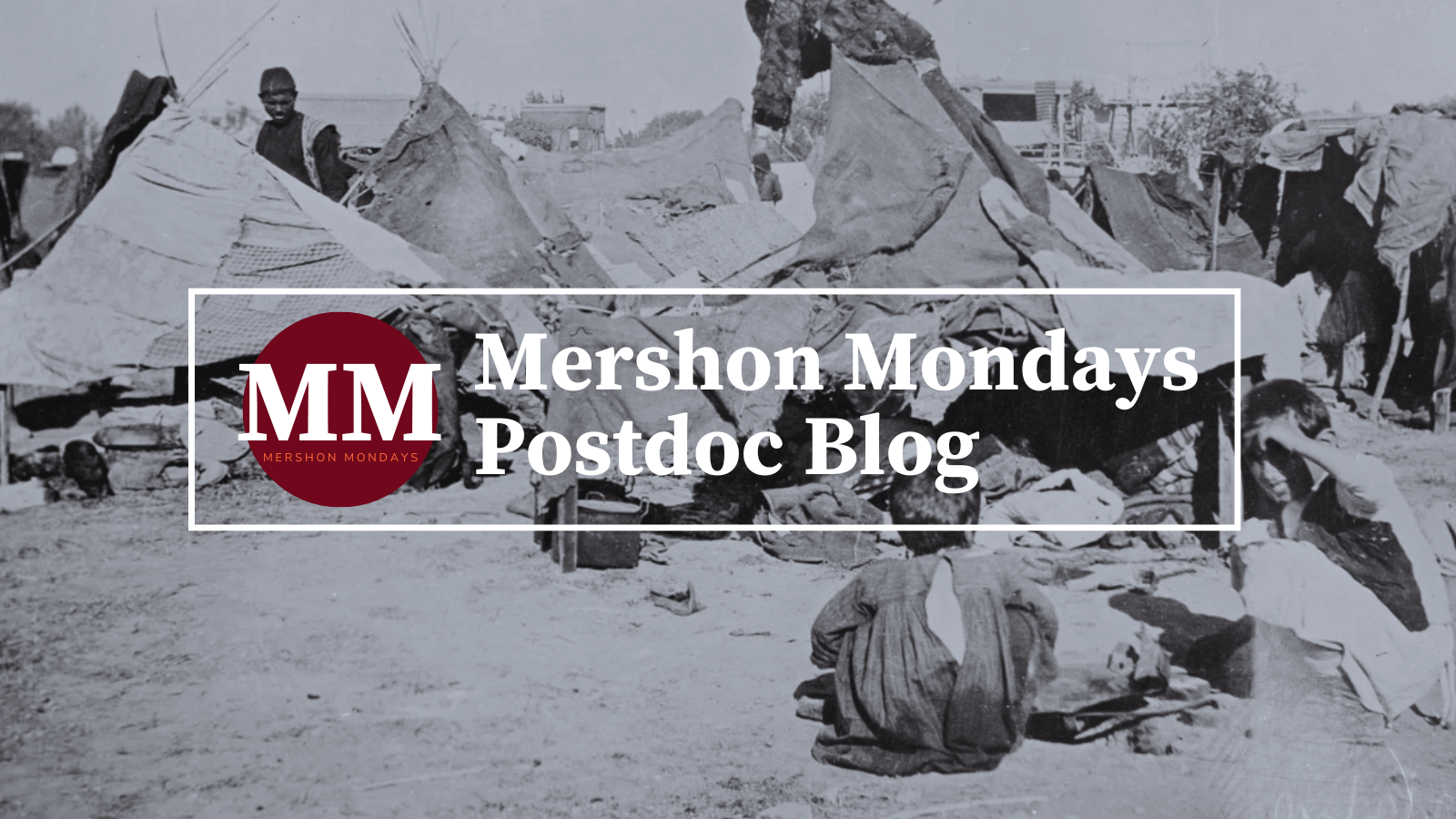

Image credit: Armenian refugees in Caucasus 1920. George Grantham Bain Collection/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (digital file no. 27082).