Jhelum and Pashmina: A River Woven into Shawls

By Parineeta Dandekar; Photos by Abhay Kanvinde

Quae loca fabulosus lambit Hydaspes

“What places the magnificent Jhelum washes!”

-Ode 1.22, Horace, Circa 3rd BC

With these lines begins M. Aurel Stein’s authoritative Ancient Geography of Kashmir, written in 1899. Stein was deeply smitten by the land and its rivers and was the first to translate Kalhana’s epic Rajatarangini—literally River of the Kings—into English.

Jhelum—or Behat, Vyeth, Vitasta, Hydaspes—has indeed washed some legendary places like Srinagar, Baramulla, Anantnag and Sopore. But it has also “washed” something very particular, something that is as much the fruit of the Jhelum as it is of Kashmir itself: the feather-light Pashmina shawl.

For the last 400 years at least, washing Pashmina shawls in the currents of the Jhelum at Srinagar has been an irreplaceable step in shawl-making. Travelers and connoisseurs of the past and the weavers and washers of today attest to the fact that it is Jhelum’s water that lends a unique softness to Pashmina. And so, Jhelum too flows through the light, warm folds of the Pashmina—adorned and loved by many, from Emperor Akbar to Queen Josephine.

Is the link between a river and an artform unbroken today?

~

While walking along the maze of new and very ancient bridges in the old Srinagar, a rhythmic whistle pierced the air. It was not coming from the Pariah kites circling overhead—an indicator of garbage and burgeoning pollution. It came from the river.

Peering down at Ali Kadal, we saw the ancient Daeb Ghat, or Washerman’s Steps. Abdul Rashid Bhat, dressed in tattered shoes and a plastic apron around his waist, was beating a fragile Pashmina on a wooden slat. He sloshed it into the Jhelum and repeated the motion. Washing is needed to free the fiber and release the natural adhesive that bind it. Every beat of the shawl on the riverbank was accompanied by a whistle. It felt like a happy laundry-day song. Ivory-white Pashminas fluttered on a clothesline on cobbled bank. The Jhelum was ink-black, yet the shawls appeared untouched, cloud-like.

Bhat told us he has been washing Pashminas here for thirty years. The polluted river water causes itching on his hands and feet, but this is his life. He is one in a long line of people who process hand-spun Pashminas. As we spoke, two people sauntered along Ali Kadal and casually dumped a sack of food into the river. The Pariah kites swooped down instantly. I shouted in disbelief. Bhat did not even look up. “This keeps happening. Someone needs to stop this.” he said.

Resting one foot on the stone step of the yarbal*, he explained that wooden slats had once been built into the steps for washing and beating Pashminas. “They were removed under the Riverfront Development Project. We tried to install something ourselves, but it’s not the same.”

The Jhelum Riverfront Development Project moves steadily along the river. Like most riverfront projects, I wonder about the logic of beautifying ghats of a river that is clearly carrying raw sewage. Nearby, an enthusiastic worker pointed out the ancient slats once used for washing Pashminas. They had been thrown into the river and lay half-submerged, resembling animal carcasses.

At another yarbal near Zaina Kadal sit Danish and Akit, brothers who trade in Pashmina and Kani shawls, carpets, and woolen pherans. “We’ve lived here for generations. We can see the river from our windows. We’ve washed Pashminas here since my grandfather’s time, at least.”

Washers employed by them toil inside the river. On the steps lie spinners and dryers. Large, bouncy bundles of freshly washed shawls sparkle on the riverbank.

“A family works at each yarbal,” they tell us. “It’s not a written contract, but an understanding. We’ve been on this yarbal for ages. Earlier, the washing and polishing of Pashmina was a secret known only to five families. Now it’s widespread. With that, the use of soaps and chemicals has increased—just as the river itself has grown dirtier.”

~

Ain-i-Akbari records the whimsy of Pashmina. It notes the riot of colors favored by Akbar and the organic dyes used—blues from indigo, yellow from Flame of the forest, green from waft tanj grass in Kashmir, orange and yellow ombrés from Indian madder and geraniums. orange-gold from wild rhubarb, rust from pomegranate and walnut rind, browns from kamila wild rose bark (Rather 2025). The color palette reads less like chemistry and more like ecology mixed with Arabian Nights.

Texts like “The Valley of Kashmir”, a sort of gazetteer recorded by Commissioner Walter Lawrence in 1895, notes the organic soaps used to wash Pashminas. Roots of plants like Sahour and Krist were used, but the colored shawls needed no soap. Soap was made locally “from alkaline ashes of pine, elm and amaranthus mixed with mutton fat and red bean flour. He records that the region around Sopore was renowned for soap manufacture.”

Pashmina wool comes from Ladakhi highlands, from the Changthang goats reared mostly by the Changpa tribe. This is an ancient trade, with records dating back to Shah-e-Hamadan, Syed Ali Hamadani, who “in 1383 is said to have brought shawl-weaving techniques from Turkistan to Kashmir and shawl wool—the limpid fleece of the kid goat—from Greater Tibet (Ladakh)” (Rather 2025).

Today, Climate change affects everyone in the long chain of shawl making. Pashmina wool comes from a specific species of goat, often referred to as Changthangi goat from the high-altitude Changthang Plateau of Ladakh. Patterns of snowfall here are changing, affecting the rearing of Pashmina goats (Newey 2022). In April 2024, protests under the banner of the Pashmina March highlighted the plight of shepherds in Ladakh who lose animals to cross-border violence. The LOC-isation of winter grazing grounds of Changpa shepherds has been calamitous for this marginal group (Syed 2022). In Srinagar, unrest affects the Pashmina trade as well.

~

Does the Pashmina only mean wool from a particular goat? Can it be made anywhere?

This is a beautiful riddle which tells a story about belonging. Traditional art forms hold affinity to the landscapes they are born in, landscapes that have nourished them. Just as Bhatiyali music blooms along Bengal’s rivers or the Chamba Rumal tells the story of the River Ravi, Pashmina bears affinity with the Ladakhi highlands, the ancient Silk Route and with the Jhelum itself.

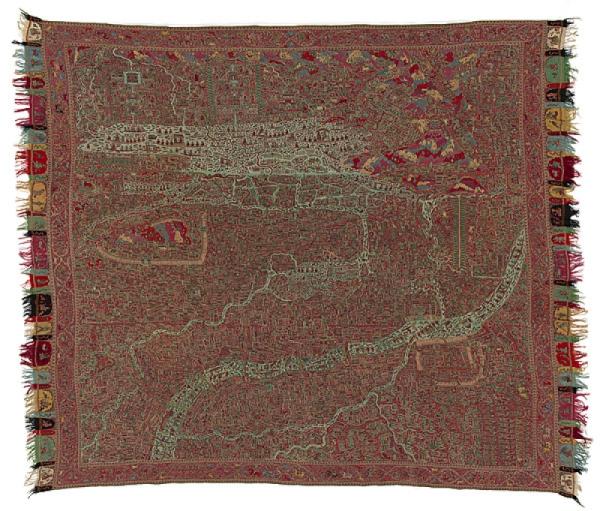

The paisley motif, so often found in Pashmina and other artforms of Kashmir, has several origin stories steeped in syncretism. One story links the graceful curve of paisley to the bend in Jhelum itself (Sharrad 2004). On the other hand, map shawls made in late Nineteenth Century often included the azure Jhelum flowing through the heart of Srinagar, with boats, bridges fish and birds (Pal 2007).

And then, there was the quality of Jhelum’s waters.

Francois Bernier, the remarkable French traveler who visited Kashmir between 1656 and 1668 wrote: “Great pains have been taken to manufacture similar shawls in Patna, Agra and Lahore; but notwithstanding every possible care, they never acquire the delicate texture and softness of the Kashmere shawls, whose unrivalled softness may be due to the specific powers of the waters of the country” (Bernier 1916).

Frank Armes writes in Woven Legends: “It was not unusual to ship textiles long distances for special processing… just as the rich dyes of the Pashmina shawls were brought to life by washing them in the Jhelum river… the special qualities of Srinagar’s waters were legendary” (Pal 2007).

Pashmina received its Geographical Indication tag in 2005. The official GI Journal of the Government of India states:

“Finally the fabric is carefully washed by the traditional washers in the running waters of the tributaries of river Jhelum… in clear, cold water on the banks of streams in Srinagar in open air.”

Several ghats and canals—Tsunth Kul, Dal Lake, Telbal stream and Mar Canal—are repeatedly mentioned in gazetteers and travelogues as prime sites for washing Pashmina.

Across India, similar river–fabric relationships exist: Machilipatnam chintz and the Krishna, Bagh prints and the Baghini, Kanchipuram silks and the Palar, Maheshwari sarees and the Narmada, Kovai Kora cotton and the Bhavani. These links live not only in stories but in GI registrations too.

~

Can the bond between Jhelum and Pashmina continue?

It is heartbreaking to see the storied Jhelum—rising resplendently at Verinag—so thoroughly decimated by human society. Solid-waste management and sewage treatment in Srinagar appear nonexistent. The ancient yarbals, those modest stairways to the river scattered through the Shehr-e-Khaas, lie in shambles. The river carries near-undiluted sewage. The riverfront project looks garish, like applying rouge to the cheeks of an unwell patient.

Our friend Babur Hussain who works of Jhelum, says, “It’s a miracle how this dirty water cleans the Pashmina.”

Does washing Pashmina contribute to pollution? It does—but the answer is nuanced. The process can easily be made river-friendly through the use of natural soaps and bio-enzymes, within a framework of environmental governance. What is missing is not tradition or technique, but governance. And it is lacking throughout Jammu and Kashmir. Polluted Jhelum is destroying the people who stand knee deep in the polluted waters to bring shine to a shawl.

Washing Pashmina on the banks of the Jhelum could be a dignified, living heritage—and even a meaningful attraction—in a city sustained by invisible labor. It is definitely not so today. Rejuvenating Jhelum would also mean rejuvenating this ancient occupation linking beauty, art, rivers, and local livelihoods.

Of all the places that Jhelum or Hydaspes washes, perhaps Pashmina is the most elusive.

Notes

* A yarbal is a stepped riverbank platform or ghat along the Jhelum and its channels in Srinagar where people historically drew water, washed clothes, and carried out daily labour—especially washing woollen textiles like Pashmina. In Kashmiri cultural memory, the word yarbal has been associated with social interaction and community life by the water. Linguistically, Yaar means “friend” in Kashmiri and Persian, and bal refers to a riverside place, suggesting a place where friends gathered by the river. Photographs and accounts from the early 20th century show yarbals as lively centers of daily life on the Jhelum, though many have fallen into disuse or disrepair in recent decade.

Bernier, F. 1916. Travels in the Mogul Empire, A.D. 1656-1668. Oxford: University Press.

Newey, A. 2022. ‘The cashmere crisis of the Changthang Plateau’, Geographical. https://geographical.co.uk/culture/cashmere-crisis

Pal, P. 2007. The Arts of Kashmir. New York: Asia Society. https://archive.org/details/artsofkashmir0000palp/page/n3/mode/2up

Rather, Sajad Subhan. 2025. ‘Dyeing and Washing Textiles in Medieval Kashmir: Unraveling the Artistic Techniques and Cultural Significance’, TEXTILE, DOI: 10.1080/14759756.2025.2588871

Sharrad, P. 2004. Following the Map: A Postcolonial Unpacking of a Kashmir Shawl. TEXTILE, 2(1), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.2752/147597504778052900

Syed, V. 2022. ‘Life at LAC: The shepherd’s struggle with dragon’, Free Press Kashmir. https://freepresskashmir.news/2022/08/26/life-at-lac-the-shepherds-struggle-with-dragon/