The United States's North Korea problem

What is North Korea going to do next?

That’s a question that we all seem to be asking a lot lately and nobody has a definitive answer as to what the country and its mercurial leadership will do.

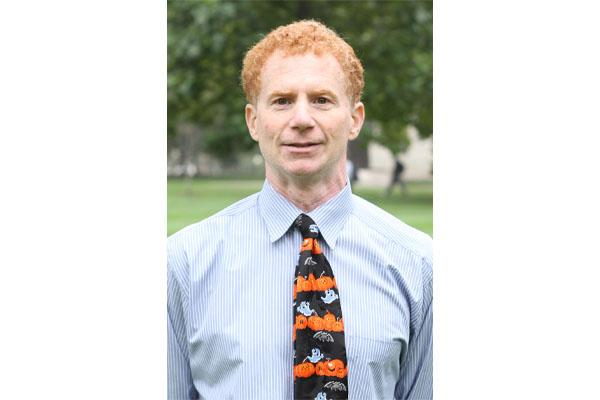

Mershon affiliate Mitchell Lerner, associate professor of history and director of the Institute for Korean Studies, brings some insight to the confusion. He believes the United States has long needed to rethink its approach toward North Korea. Lerner, who is the director of Ohio State’s Institute for Korea Studies, recently authored a column in the Washington Post that called for the United States to curb its expectations of China solving the problem.

Lerner recently offered his take on the ever-developing situation with North Korea.

Q. At the end of July, North Korea fired an intercontinental ballistic missile that experts believe could have reached as far as the United States. Was this unexpected?

A. The missile reportedly crashed into the ocean off the coast of Japan, after reaching a height of about 2,300 miles. The success took many in the global community by surprise, as did the news from a recent intelligence estimate putting forth that North Korean leader Kim Jong Un controls about 60 nuclear weapons now — more than anyone had previously thought. (By comparison, the United States has about 6,800 nuclear warheads — and Russia about 7,000.)

The United States, like many others, did not expect North Korea’s weapons program to have made such advancement this quickly, according to Lerner.

“Yes, it is unexpected how quickly they have advanced their (nuclear weapons) program,” he said. “We have known for a long time that they were moving in this direction, but this represents some really striking success.”

But to some extent, this could also be viewed as inevitable, Lerner said. North Korea is dedicating a huge percentage of its GDP towards weapons development — something that other nations have not done or are not willing to do.

“It’s not a nation that has ever spent much time worrying about the fortunes of its people or of the long-term development of its economy or infrastructure,” said Lerner. “It’s very much focused on developing its weapons capabilities at the expense of pretty much everything else. It’s one of the defining principles of the nation over the past few decades.”

Q. How alarmed should the United States be about this advancement?

A. Concern is a very appropriate reaction, given North Korea’s unexpected progress in advancing its nuclear weapons program. “But that doesn’t mean that they have demonstrated the ability to mount a nuclear warhead on it and launch it at a target with some accuracy,” said Lerner. “Nor have they demonstrated the technology for successful re-entry into the atmosphere.”

“It doesn’t appear that they have put all those components together,” he continued. “But they are clearly a lot closer than they were … and a lot closer than I’d like them to be.”

Q. Can the United States depend on China for help in reining in North Korea in the future?

A. Probably not. U.S. leaders have long maintained that China could help rein in or put pressure on North Korea. But Lerner doesn’t think China is the solution. China doesn’t seem to have the type of influence over North Korea that’s needed — and China has its own strategic interests when it comes to preserving the North Korean government.

“The result is the same, that this kind of subcontracting of the problem to China isn’t the answer,” he said. “The U.S. needs to step up and recognize that there are some tough decisions that need to be made here.”

Q. Will the U.N.’s new sanctions make a difference?

A. About a week after North Korea tested the rest of the globe’s nerves by firing off the intercontinental missile, the U.N. took action. On Aug. 5, the United Nations Security Council voted 15-0 — which included both China and Russia, as well as the United States — to significantly increase economic sanctions on North Korea. The sanctions affect one-third of North Korea’s approximately $3 billion in annual exports, which include coal and seafood.

It’s definitely a step in the right direction, according to Lerner. But it’s not the first time that other nations have committed to sanctions against North Korea and then didn’t really enforce them. Plus, sanctions may not have the same impact on a nation like North Korea as they would on another nation, given North Korea’s ties to the international black market and its leadership’s disinterest in the welfare of millions of its own citizens.

“I admit to not being optimistic that [sanctions] will really have the impact that the U.S. wants,” said Lerner. “Still, it is certainly worth trying.”

Lerner noted he doesn’t think that sanctions or pressure on China to get involved or even working with allies in the region, such as South Korea and Japan, to further isolate North Korea will ultimately be successful.

Why not? “Because North Korea doesn’t really care what the outside world is doing to it,” he said. “Short of war, the North is going to continue to do what it wants to do. There’s not a lot that’s ever been shown to put much restraint on them.”

Q. Where do we go from here?

A. President Donald Trump has already responded to the latest developments with anger and threats, promising a show of force if North Korea doesn’t draw back. “As I said, they will be met with the fire and fury and power, the likes of which this world has never seen before,” Trump said on Aug. 8.

Does that mean a military attack is imminent? It’s hard to say for certain, but the consequences of a military strike are sobering enough to make it unlikely unless the North does something militarily to provoke one, Lerner said.

“I think this is all bluster,” he said. “The administration wants [North Korea]—and the world— to know that all options remain on the table, in case the threat of an attack helps push North Korea to talk, even a little bit. I don’t think anyone thinks it will, but the U.S. will at least keep trying to send that message.”

This story first appeared in Ohio State Insights.